United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Crisis in Darfur

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum is a living memorial, dedicated to honoring the victims of the Holocaust. One vital way it fulfils this mission is by confronting threats of genocide and related crimes against humanity today.

When Google Earth was first released in June 2005, the Museum's Academy for Genocide Prevention was exploring how foreign policy professionals could better share information about emerging threats of genocide and mass atrocities. The Museum recognised Google Earth's potential to help organise and present information in a compelling and timely way, and to serve as an effective vehicle for public outreach and education about genocide and related crimes against humanity.

Crisis in Darfur, a project of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum's Genocide Prevention Mapping Initiative, is an unprecedented effort by the Museum and Google to illuminate the genocide in Darfur by bringing together satellite imagery with layers of data and multimedia in Google Earth. This partnership will, in a very visual way, draw attention to threats of genocide around the world, and promises to transform how information about mass atrocities is shared and presented in the future.

During the crisis, more than 300,000 people were killed and 2,500,000 driven from their homes in the Darfur region of western Sudan. Throughout Darfur, more than 1,600 villages have been damaged or completely destroyed. The lives of those displaced still hang in the balance, while violence continues to affect remaining villages across Darfur, as well as the sprawling refugee camps throughout the region and neighbouring Chad.

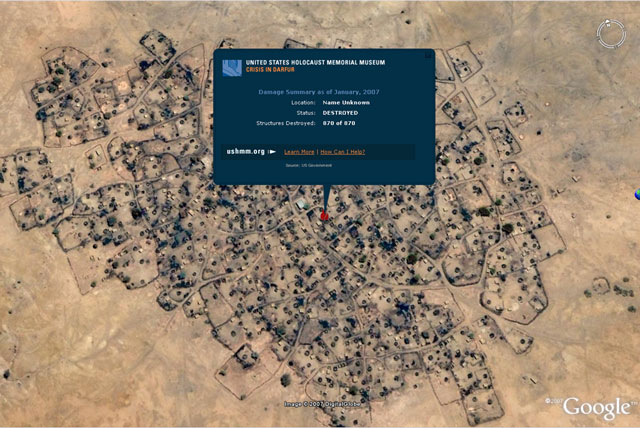

Typically, perpetrators of genocide operate under a cloud of denial and deception. The Sudanese government maintains that fewer than 9,000 civilians have been killed in the 'civil war' in Darfur. Claims like these are easily refuted when any citizen worldwide can view high-resolution satellite imagery and other critical evidence which was previously accessible only to a limited few. Now, any user of Google Earth can zoom down to Darfur and see the extent of the destruction, village after village.

How they did it

Development began in earnest when an international volunteer organisation – the BrightEarth Project was formed to explore how a new generation of mapping tools, including Google Earth, could empower citizens around the world to better defend vulnerable populations. Participants included museum staff, as well as Declan Butler, a senior science reporter at Nature Magazine, Stefan Geens, a blogger who runs the popular blog www.ogleearth.com, and GIS professionals Mikel Maron, Timothy Caro-Bruce, and Brian Timoney.

Working with United Nations agencies, the US Department of State and non-governmental organisations, the Museum obtained data that had been available only in scattered locations and in diverse formats, including paper maps, tables and text.

Museum staff and Bright Earth volunteers worked for more than a year to bring together data on village destruction, locations of refugee camps, humanitarian access and more and created the first KML draft layers in early 2006. It was the first time that all this imagery, data and multimedia had been brought together in the same place.

But without high-resolution imagery, presenting the data in Google Earth was only a slight improvement over traditional maps. Google agreed to prioritise imagery acquisition for Darfur and between autumn 2006 and spring 2007 the Google Earth team updated large swaths of Darfur with high-resolution imagery.

With the imagery alone, it was next to impossible to locate the attacked villages. With the data alone the user could see the big picture of attacks in Darfur but had no understanding of the local impact on each village and settlement. When the two sets of data were combined, each became more powerful.

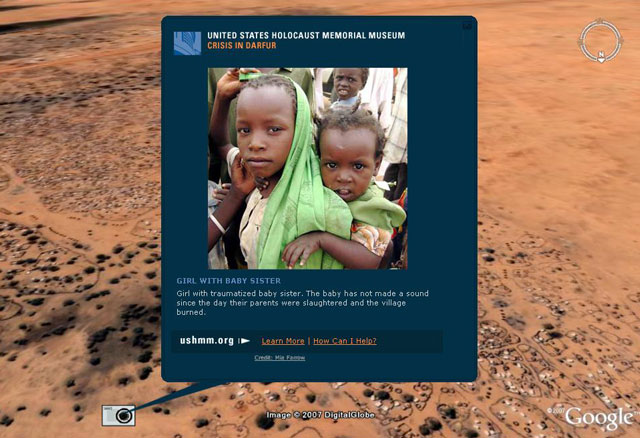

Images of the charred remains of village after village provided undeniable proof of the extent of destruction and its aftermath, with hundreds of thousands of tents in refugee camps dotted across the region. By bringing together geo-referenced photos and videos from Museum staff and acclaimed international photographers, as well as testimonies from Amnesty International, the stories of what happened to these villages became more personal and compelling.

Crisis in Darfur is the Museum's first attempt at helping to humanise the victims of genocide through Google Earth. Now the Museum is working on innovative ways to update the layers to better help survivors, aid workers and those under threat of genocide in Darfur and around the world to share their stories.

“

“One of more than 1,600 damaged or destroyed villages in Darfur; more than 100,000 homes have been destroyed.

”No one can any longer say they don't know. This tool will bring a spotlight to a very dark corner of the earth, a torch that will indirectly help protect the victims. It is David versus Goliath, and Google Earth just gave David a stone for his slingshot.

”John Prendergast, International Crisis Group (Washington Post, 14 April 2007)

Impact

Once Google Earth agreed to feature the Museum layers as default content for every Google Earth user, it was clear that this project would have a major impact around the world.

Crisis in Darfur was launched on 10 April 2007. The launch was covered worldwide by more than 500 media outlets in English alone and in many other languages, from Dutch to Arabic. Hundreds of blogs picked up the news, and teachers, aid workers and activists are now regularly using Google Earth to help show what genocide looks like. More than a million people have downloaded additional layers from the Museum's Web site, and more than 100,000 have visited the "What Can I Do?" page to find out how they can help.

Two months after the launch, the Museum's Web site was still receiving 50% more traffic than before. The project had significantly expanded the global reach of the site – over a year the percentage of the visitors from outside the UShad jumped from 25% to 46%. The number of hits from Sudan alone increased more than tenfold.

This reaction shows that web users worldwide are hungry for more applications of technology that connect them to what is happening in the world in more meaningful and personal ways. While Google Earth users can still enjoy zooming down to their homes, looking up restaurants, and viewing cities in 3D, now they can also understand the greater potential of a 'virtual globe' when they see for themselves what is occurring in Darfur.

Google Earth is beginning to be used by United Nations agencies to organise and share critical information in the field and headquarters, as well as by some non-governmental organisations. But the use of Google Earth as a tool to prevent genocide still remains limited.

Google Earth, when combined with new participatory Web 2.0 approaches, could help transform operational response and early warning by providing collaborative and dynamic ways for communities to come together, share critical information and help citizens see the world in a new light.

Improving rapid access to satellite imagery has the potential to enable citizens worldwide using Google Earth to play a part in monitoring areas at risk of genocide, and to strengthen organisations' ability to respond effectively. Expanding the use of remote imagery might help convince potential perpetrators that their actions against civilians will not go unnoticed by the international community. And finally, these efforts might also contribute to building a credible and globally accessible public record that supports accountability following crimes against humanity, genocide and other abuses.

“

“Children of Darfur

”